NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Walker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JW, editors. Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations. 3rd edition. Boston: Butterworths; 1990. Bookshelf ID: NBK370 PMID: 21250211

Definition

X-rays are a form of electromagnetic radiation. They have a very short wavelength located just before the far ultraviolet band on the electromagnetic spectrum.Technique

The standard x-ray examination of the chest consists of a frontal (PA) and lateral view. The frontal view is called a PA view because the patient stands with the anterior chest on the cassette and the back to the x-ray beam. The x-rays first hit the posterior and then the anterior chest before hitting the cassette; thus the name PA. The cassette is 6 feet from the x-ray tube. The lateral film is taken the same way except the patient is standing with his or her side perpendicular to the x-ray cassette. Unless otherwise specified, a left lateral is taken. An AP film of the chest is the usual technique when patients are too ill to leave the bedside. It is usually taken with the cassette behind the patient and the x-ray beam 40 (rather than 72) inches from the cassette, thus magnifying all structures.An apical lordotic technique is used to evaluate the apices of the lungs. The x-ray beam is angled in a slightly upward projection, causing anterior thoracic structures to be projected above the posterior thoracic structures. The clavicle and first several sets of ribs are projected above the apices of the lung, allowing a good view of this area. It is particularly useful in evaluating the upper lobes for evidence of tuberculous disease. The lateral decubitus technique is one in which the patient is placed lying on the cassette with either the left or right side dependent. It is most frequently used for evaluating the presence of free-moving pleural fluid. The usual technique is to have the patient lie on the side with the fluid and look for a radiodense fluid line along the dependent side. With small amounts of pleural fluid, it is helpful to have the patient lie with the normal side dependent and see if the diaphragmatic angle on the involved side becomes sharp, thus indicating the presence of a small, free-moving effusion.

The closer an intrathoracic structure is to the cassette, the sharper and more accurate will be its image on the cassette. This is because as x-rays strike structures, they travel in a slightly divergent rather than totally parallel manner. Therefore, the further the distance between an object and the cassette, the greater the amount of magnification and the lesser the sharpness that object's image is represented on the cassette. Hence, the cardiac silhouette appears larger and less sharp on an AP than a PA film. Similarly, a right-sided process is better defined in the right and not the left lateral position.

When a chest x-ray is taken with optimal technique, the intervertebral spaces should be barely visible through the cardiac silhouette. If the intervertebral spaces are not apparent, then the film is relatively light. This means that an existing infiltrate may seem more prominent, or it may appear that an infiltrate is present when in fact there is just normal vasculature. In other words, a light film is more likely to be overread. When one can very clearly see the intervertebral space and outline the vertebral bodies, then the x-ray is somewhat overpenetrated. This tends to make an infiltrate appear less prominent, or sometimes even cause the infiltrate not to be appreciated on the film. In other words, a dark film is more likely to be underread. The above guidelines for over- and underpenetration should be kept in mind when comparing the progression or resolution of a process on serial films.

Basic Science

In 1895 Wilhelm von Roentgen described x-rays and ushered medical science into a new era of technology. By 1896, physicians in the United States were already putting Roentgen's discovery to clinical use. Today the chest x-ray is the most frequently requested radiologic examination, accounting for one-quarter to one-third of all x-ray procedures. We have indeed come a long way since that November day in Wurzburg when Roentgen made his first observations of these magical rays that could pass through objects opaque to light and cause a visible fluorescence.X-rays are produced by bombarding a tungsten filament with an electron beam. While x-rays and visible light are both forms of electromagnetic radiation, they have different physical properties. These different properties make the x-ray medically useful. Specifically, many substances opaque to light can be penetrated by x-rays. As the x-ray traverses the thoracic cavity, it hits the structures in its path; in doing so, part of its energy is dissipated. The thicker and denser the structure, the greater the amount of energy dissipated. Once it has traversed the thoracic cavity, the x-ray strikes the film; metallic silver is precipitated photochemically within the gelatinous emulsion on the film.

In clinical practice the x-ray film is put in a cassette that contains a fluorescent coating in front and in back. This coating is activated by the x-rays that cause it to emit light rays that reinforce the photochemical effect. If the x-rays traverse the thorax without going through much tissue, they will strike the cassette with a relatively large amount of energy, and when the cassette is developed, this area will be black. Conversely, an x-ray that has passed through a very dense and thick thoracic structure will have a much lower energy when it hits the cassette and will look white. Structures of intermediate density and thickness will give intermediate or gray appearances. These varying shades of black, white, and gray provide contrast on the x-ray film. A film taken with suboptimal x-ray voltage (i.e., a white or underpenetrated film) results in an x-ray where the intrathoracic structures have hazy borders and are difficult to differentiate from adjacent structures. Conversely, a film taken with too much voltage (i.e., an overpenetrated or black x-ray) will result in a radiograph that has relatively little contrast, making differentiation of intrathoracic structures difficult.

Normal Radiographic Anatomy

Before examining a chest x-ray for signs of disease, acquaint yourself with the normal anatomy. The right lung is divided into an upper, a middle, and a lower lobe; the left lung is divided into an upper and lower lobe. The lingula, anatomically part of the left upper lobe, is the analog of the right middle lobe. The lobes are separated from each other by septa. Visceral pleura from the surfaces of adjacent lobes form the interlobar septa. The space between is called the interlobar fissure, although the terms septum and fissure are used synonymously. The septa have an average thickness of about 0.2 mm (see Figures 48.1 and 48.2).The major (or oblique) fissure of each lung separates the lower lobes from the middle and upper lobes on the right, and from the upper lobe on the left. The major fissure can usually be seen on the lateral view where it normally runs from about the level of the fifth thoracic vertebra or fifth rib interspace, crossing inferiorly and anteriorly parallel to the sixth rib to reach the diaphragm a few centimeters behind the anterior costophrenic angle. The oblique fissure presents a smooth, concave surface as it courses around the lung. Anterior or posterior deviation of this fissure often represents loss of volume in the lung segment toward which the fissure is deviated. The minor (or horizontal) fissure can be seen in 50 to 60% of PA and lateral chest x-rays. On the PA view its normal position is between the second and fourth anterior ribs, presenting a slightly convex but horizontal appearance. When there is loss of volume, the minor fissure will be drawn out of its normal horizontal position; it is pulled up with upper lobe volume loss and down and posteriorly with lower lobe volume loss.

Assessment of pulmonary vasculature can be a difficult and confusing task. Pulmonary arterial segments converge toward the hila and meet in the right and left main pulmonary arteries. The left pulmonary artery is slightly higher than the right 97% of the time. This means that the right hilum is never normally higher than the left. If the right hilum is higher than the left, then something is either pulling (or pushing) the right hilum up or something is pulling (or pushing) the left hilum down. The hila are best appreciated on the lateral projection (see Figure 48.3). In the lateral view, the right and left upper lobe bronchi can be seen as two circular radiolucent areas with the right above the left. The right pulmonary artery can be seen projecting anteriorly above the upper lobe bronchi; the left pulmonary artery projects posteriorly. The inferior vena cava can also frequently be seen on the lateral view, coursing up from the left hemidiaphragm to join the posterior cardiac silhouette. On the PA projection the superior vena cava can sometimes be seen coursing superiorly from the hila.

The right hemidiaphragm is normally slightly higher than the left in about 90% of cases. The diaphragm normally has a smooth and convex contour that tapers to give a sharp costophrenic angle. With a good inspiratory effort, the level of the diaphragm should be near the level of the ninth posterior rib.

The trachea is normally midline on the PA or AP film. The tracheal air shadow is readily visible on the normal PA film, and under normal circumstances the spinous processes of the vertebral bodies will be located in the center of the tracheal lucency. If the tracheal air column is deviated, you must determine if this is secondary to pathologic change or rotation of the patient. On a well-centered PA chest film the ends of both clavicles will be equidistant from the spinous processes of the vertebral bodies. Therefore, when you notice deviation of the tracheal air column, check if the spinous processes of the vertebral bodies maintain these relationships with the clavicles. If this is the case, then there is true tracheal deviation; if not, then the patient is rotated toward the clavicle farthest from the spinous processes.

Radiographic Interpretation

The chest x-ray is a two-dimensional, static, black-and-white representation of a three-dimensional, dynamic living structure. Our job is to take these two-dimensional, black-and-white images and reconstruct what is going on inside the patient's chest. Most people accomplish this by "pattern reading." This involves learning the radiologic patterns of various pathologic entities. For example, one sees a blunted costophrenic angle, and one instantly comes up with the diagnosis of pleural effusion. Or one sees a fluffy, mottled density in the right lower lobe and comes up with the diagnosis of pneumonia. While this method can lead to the correct diagnosis a good percentage of the time, someone faced with a difficult x-ray, or who sees something with which he is not familiar, will be at a total loss. This is very similar to programming a computer to recognize patterns and then giving it a pattern it has never seen before. It will not be able to come up with the diagnosis.The optimal way to read x-rays is to learn certain radiographic principles and then apply these principles in a logical and consistent manner to reading x-rays. If you do this, you should almost always be able to come up with the diagnosis, even if you have never seen it before. Air, water or tissue, and bone are three basic radiologic densities. Air density, as represented by the lung parenchyma, is black on the x-ray. Bone density is white on the x-ray. Water or tissue density is gray on the x-ray. We must keep in mind that the thickness of a structure also affects its projected density on the x-ray film. Even though the heart is less dense than bone, it is projected whiter on the chest x-ray because it is significantly thicker than the ribs or vertebral bodies. We can see the borders between the various intrathoracic structures because of this difference in contrast.

Dr. Benjamin Felson (Felson and Felson, 1950) described the now-famous silhouette sign: "An intrathoracic lesion touching a border of the heart, aorta, or diaphragm will obliterate that border on the roentgenogram. An intrathoracic lesion not anatomically contiguous with the border of one of these structures will not obliterate that border. We have applied the term silhouette sign to indicate the loss of the silhouette of any of these borders by adjacent disease" (p. 364). By using the silhouette sign, one is able to locate a pathologic process on a single x-ray view. For example, a right middle lobe infiltrate will obliterate the right heart border as outlined by the silhouette sign, whereas a right lower lobe infiltrate will not. This is because both the right middle lobe and the right heart border are anterior and adjacent structures, and when there is water density in both structures, the borders between the two become obliterated. Thus, on a PA view of the chest, we can locate any structure in the superioinferior dimension as well as the mediolateral dimension, and the silhouette sign allows us to locate it in the posterioanterior dimension. This can be corroborated by looking at the lateral film.

By using a systematic approach to the reading of the chest x-ray, one can usually easily define the pathology. Define an abnormality on chest x-ray by asking a series of questions. First, is it an intraparenchymal or extraparenchymal process? One can see 360 degrees around an intraparenchymal process because it is surrounded by aerated lung, thus providing contrast. By definition an extraparenchymal process has one border either on the mediastinum, diaphragm, or pleural surface, and so one can see only about 180 degrees around it. In addition, intraparenchymal processes are usually projected on the PA or AP film as greater in their mediolateral dimension than their superioinferior dimensions. Therefore, the second hallmark of an intraparenchymal process is that it is usually wider than it is long. Conversely, an extraparenchymal process that is either in the pleural, mediastinal, or soft tissue space tends to be longer than it is wide. Next, ask whether the process is a mass or an infiltrate. This differentiation is easily made. A mass has a homogeneously white density; an infiltrate has a mottled, black-and-white density. The exception to this rule is a consolidation, which is a special form of infiltrative process in which all the alveolar spaces in the involved bronchopulmonary segments are involved, thus giving a homogeneously white appearance. If the process is a mass and one can see all the way around it, then it is a parenchymal mass. If it is a mass and one cannot see all the way around, it is either a hilar, mediastinal, pleural, or soft tissue process, depending on its location.

If it is an infiltrative process, then ask if it is alveolar or interstitial. The hallmark of an alveolar filling process is the presence of air bronchograms. The air bronchogram is another term coined by Dr. Felson (1973). He states that "parenchymal consolidation may result in the visualization of these bronchi (normally invisible) since the air within their lumens will stand out in contrast to the surrounding opaque lung" (p. 60). Finding air bronchograms in an area of infiltration is not as easy as it sounds and is frequently the cause of disagreement among radiologist and clinician alike. An easy way to detect the presence of an alveolar infiltrate is to use the fact that it tends to obliterate the borders of the normal blood vessels in that area. This is because of the silhouette sign described above. The alveolar filling process causes a water density around blood vessels, and so the borders of these vessels are not visualized as sharply. Unlike an alveolar infiltrate, an interstitial infiltrate tends to accentuate the vascular markings in the area of infiltration. Because alveolar and interstitial infiltrates have opposite effects on the visibility of pulmonary vasculature, this is of great help in differentiation. Although the above rules will not always hold true, they will aid the beginner and inexperienced clinician in making sense of the chest x-ray.

Clinical Significance

Now that you have mastered some basic radiologic principles of interpretation, let us put them to clinical use. With the exception of pulmonary edema, alveolar infiltrates tend to be localized, whereas interstitial infiltrates tend to be diffuse. Certain other characteristics of an infiltrate may be helpful in the differential diagnosis. Location of an infiltrate is of prime importance. Tuberculosis is far more common in the upper lobes than in any other lobes. In addition, the tubercle bacillus favors the superior or posterior segments and will rarely be seen in the anterior segment alone. The superior segment of the lower lobes and the posterior segment of the upper lobes are the most frequently involved segments with aspiration pneumonia. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia is the most frequently seen as a diffuse interstitial infiltrate.The character of the infiltrate is also important. A consolidative infiltrate is most commonly seen with a bacterial pneumonia. The presence of multiple lucent areas within a pneumonic infiltrate suggest a necrotizing process. One would think of tuberculosis, proteus, and pseudomonas, as well as anaerobic pulmonary infections. An alveolar infiltrate in an area of severe emphysema can simulate a necrotizing process because the dilated alveolar spaces of the emphysematous process can simulate cavities.

When evaluating a pulmonary mass, the most important thing to try to exclude is a neoplastic process. The presence of dense central calcification is one of the most reliable signs that a mass is not malignant. A calcified mass most frequently represents an old healed and clinically inactive inflammatory process. If there is no calcium present, one must rely on previous chest x-rays to see how long the mass has been there and if it is growing in size. As a general rule, if a mass is seen on an older film and is unchanged in size for 4 to 5 years, it is most likely a benign process, and invasive investigation of the mass is not mandatory. If old films show that the mass was smaller previously and is now growing, or that it was not present previously, then invasive investigation is mandatory. A mass on a chest x-ray of a cigarette smoker should be considered cancer until proven otherwise. The same is true for a pulmonary mass with a pleural effusion or mediastinal node in a smoker.

Cavitation within a mass most frequently represents either a necrotizing infectious process or a cavitating neoplastic lesion. When a carcinoma cavitates, the walls of the mass are thick and irregular; when an inflammatory process cavitates, the walls are thinner and more regular.

One of the more difficult things to determine is whether a hilar mass represents a large pulmonary artery or an enlarged mediastinal node. On the PA or AP projection, if you can clearly see vessels going into and joining the mass, it is more likely to be a vascular structure. One can also perform fluoroscopy on the patient and have him or her perform a Valsalva maneuver. If the structure compresses with a Valsalva maneuver, it is more likely to be venous. Similarly, if one appreciates pulsations of the structure, it is more likely to be arterial. Nevertheless, one must be careful that these are not transmitted pulsations from a vascular structure underneath the mass. The lateral view is by far the more helpful view in evaluating the hilar area. The large pulmonary arteries can be appreciated on the lateral view as a large vascular shadow, as described previously. Tumorous enlargement of the hila area can be appreciated much earlier and with greater ease on the lateral.

Volume loss of the pulmonary parenchyma is caused by one of three pathophysiologic processes: obstruction, compression, or contraction. Obstruction of a lobar or segmental bronchus will result in a resorption of the air distal to the obstruction with loss of volume of the involved segments. This is seen most commonly with an endobronchial carcinoma; however, extrabronchial masses can cause bronchial obstruction by extrinsic compression. Compression of the parenchyma occurs with a pleural effusion or pneumothorax. Contraction or scarring of the lung occurs as a sequela of a previous inflammatory process such as tuberculosis. With compression there may be obvious signs of pleural effusion or pneumothorax. With contraction there will be the interstitial infiltrate from the fibrous scarring. Volume loss from endobronchial obstruction has several direct and indirect radiologic signs.

Dr. Felson has thoroughly described the radiologic signs of obstructive volume loss (see Table 48.1). Displacement of the fissures is the most reliable sign of volume loss. The fissure is displaced toward the affected segment. For example, with upper lobe collapse the major fissure is pulled superiorly and anteriorly toward the collapsed upper lobe; in lower lobe collapse the major fissure is pulled inferiorly and posteriorly toward the collapsed lower lobe. An increase in radiodensity in the affected segment occurs because, as the segment loses volume, the tissues in that segment come closer together and hence are more dense. The final direct sign of volume loss is vascular or bronchial crowding in the effected segment. This occurs for the same reason as the increase in radiodensity.

Of the indirect signs of obstructive volume loss, hila displacement is the most reliable. The hilum is displaced upward with upper lobe volume loss and downward with lower lobe volume loss. Elevation of the hemidiaphragm is more pronounced with lower lobe volume loss than with upper lobe volume loss. Shift of the hilum and mediastinal structures toward the side of major volume loss is frequent. When there is major volume loss in one lobe, the adjacent lobe will frequently overdistend to take up the vacated space of the collapsed lobe. This results in overdistention of a normal segment, giving a more radiolucent appearance. This is known as compensatory emphysema. Armed with the above principles and a knowledge of bronchial and lobar anatomy, one can adequately evaluate a lobar or segmental collapse.

A pneumothorax is air loculated between the visceral and parietal pleura. The air is either introduced from the outside (as with chest trauma) or from the inside (as with a bronchopleural fistula). The hallmark of a pneumothorax is an area on the chest x-ray that has no pulmonary vasculature. One always feels more secure in making this diagnosis when one can actually visualize the lung parenchyma medial to the area of pneumothorax; however, this is not always the case. Sometimes it is necessary to "hot light" the film. This involves putting the film up to a strong light source, such as a 100-watt bulb, to look for the edge of the lung. With the increased light behind the x-ray, you can sometimes see the lung edge that was not appreciated on the view box. With small amounts of pneumothorax, there is no appreciable shift of the lung or mediastinal structures. With larger amounts of pneumothorax, the lung and mediastinum are pushed toward the contralateral chest as the volume and pressure within the pneumothorax increases. This results in deviation of the trachea and mediastinal structures, as well as compression of the contralateral lung with extreme degrees of pneumothorax. This is a critical situation known as tension pneumothorax. Immediate therapeutic measures must be taken to decompress the affected side at this point. One condition that causes confusion with pneumothorax is extensive bullous disease of the lung. Bulla and cysts of the lung are large, air-containing sacks within the lungs. They are the end results of various pathophysiologic processes. Sometimes these bulla or cysts can reach huge proportions and can simulate a pneumothorax. Because these bulla and cysts contain air, you will not see any pulmonary vasculature within them; however, if you look carefully, you can appreciate the walls of these bulla and cysts on the radiograph. There are none with pneumothorax. At times this can be a difficult differentiation.

References

- Felson B, Felson H. Localization of intrathoracic lesions by means of the postero-anterior roentgenogram: the silhouette sign. Radiology. 1950;55:363–74. [PubMed: 14781343]

- Felson B. The lobes and interlobar pleura: fundamental roentgen considerations. Am J Med Sci. 1955;230:572–84. [PubMed: 13268436]

- Felson, B. Chest roentgenology. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders, 1973.

- Felson B. Radiologic evaluation of pleural disease. J Respir Dis. 1982;3087:41–47.

- Proto A, Tocino I. Radiographic manifestations of lobar collapse. Semin Roentgenol. 1980;15:117–73. [PubMed: 7394541]

- Squire L. Fundamentals of roentgenology. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1966.

Figures

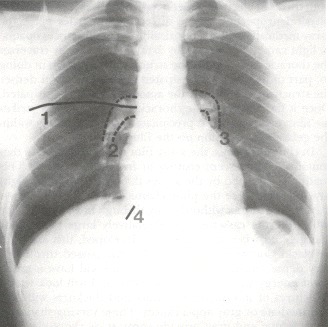

Figure 48.1

(1) Minor fissure. (2) Right pulmonary artery. (3) Left pulmonary artery. (4) Inferior vena cava.

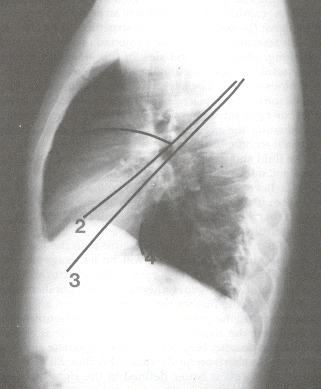

Figure 48.2

(1) Minor fissure. (2) Right major fissure. (3) Left major fissure. (4) Inferior vena cava.

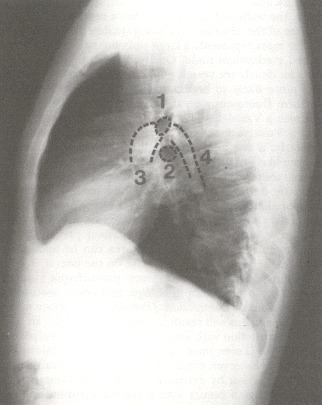

Figure 48.3

(1) Right upper lobe bronchial orifice. (2) Left upper lobe bronchial orifice. (3) Right pulmonary artery. (4) Left pulmonary artery.

Tables

Table 48.1Roentgenographic Signs of Loss of Lung Volume

| Direct signs |

Displaced septa Displaced septa |

Increased radiodensity in affected lobe Increased radiodensity in affected lobe |

Crowding of vascular and bronchial markings Crowding of vascular and bronchial markings |

| Indirect signs |

Unilateral hemidiaphragm elevation Unilateral hemidiaphragm elevation |

Deviation of the trachea Deviation of the trachea |

Shift of the heart and mediastinum Shift of the heart and mediastinum |

Hilar displacement Hilar displacement |

Copyright © 1990, Butterworth Publishers, a division of Reed Publishing.

Không có nhận xét nào:

Đăng nhận xét