NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Walker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JW, editors. Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations. 3rd edition. Boston: Butterworths; 1990. Bookshelf ID: NBK356 PMID: 21250197

The diagnosis of pulmonary diseases and disorders requires the integration of pulmonary history and physical examination data acquired at the bedside with data provided by chest roentgenograms and the pulmonary function and blood gas laboratories. Taken together, these modalities provide a framework for generating and pruning a differential diagnosis and for planning therapy.

Dyspnea (Chapter 36), the subjective sensation of difficulty in breathing, is probably the most common respiratory complaint and cannot be differentiated at first glance from dyspnea due to cardiac disease, neuromuscular weakness, or simple obesity. Dyspnea should always be quantified as to how much exertion is necessary to produce the sensation of breathlessness.

Wheezing and asthma (Chapter 37) point to the presence of an obstructive airway process but may be seen in heart failure as well. Wheezing may result from airway reactivity, airway narrowing, airway obstruction, compression, tumors, aspirated foreign bodies, as well as a variety of biochemical and immunologic insults. The time course of wheezing complaints and history of precipitating causes provide important information for interpretation.

Cough and sputum production (Chapter 38) are common to obstructive, inflammatory, infectious, and neoplastic pulmonary processes, as well as cardiac diseases and disorders of the ears, nose, and throat. Cough is a normal defense mechanism of the respiratory tract, but when increased in severity or frequency, cough can be a cause of disease as well as an indicator of disease. Sputum production reflects the presence of inflammatory, infectious or neoplastic disease in the airways or pulmonary parenchyma. The amount and character of sputum provide the physician with helpful clues to distinguish among possible etiologies.

Hemoptysis (Chapter 39) is never normal and can be a warning of a serious or even life-threatening respiratory disorder. Hemoptysis must be differentiated from hematemesis and from simple epistaxis, and must be quantified in terms of volume per 24 hours for adequate assessment.

Tobacco use (Chapter 40) is probably the most prevalent cause of chronic lung disease in the United States and the most important avoidable cause of respiratory morbidity today. The risk of serious pulmonary diseases including lung cancer and emphysema is directly related to the number of cigarettes a patient has smoked. Smoking should be quantified in terms of pack years, packs per day multiplied by the number of years smoked. Smoking of substances other than tobacco is also a potential cause of morbidity. Use of marijuana, cocaine, and other inhalable drugs should also be considered.

Environmental inhalation (Chapter 41) is a significant cause of respiratory diseases. Coal miners ("black lung"), quarry workers (silicosis), insulation installers and shipyard workers (asbestosis), and cotton mill workers (byssinosis) represent notable risk categories. A thorough work history should be a part of every clinical evaluation, especially when unexplained respiratory complaints are present. Environmental exposures may be either sustained or episodic. The examiner should inquire carefully about the relationship of symptoms to specific exposures. In particular, a detailed occupational history is important in patients where an etiology is not readily apparent. The actual job performed as well as job title should be explored.

Past pulmonary disease (Chapter 42) contributes background information that is helpful in assessing a current complaint. Knowledge of prior respiratory infections or prior chest film abnormalities is invaluable in the interpretation of a current problem.

In settings where tuberculosis remains prevalent, knowledge of a history of tuberculosis (Chapter 47), tuberculosis exposure, and tuberculin skin test results may prove crucial.

Symptoms of infections such as fever or chills may be important evidence in the evaluation of a productive cough, and the presence or absence of weight loss or loss of appetite may serve to underscore the seriousness of a particular complaint or objective abnormality. Because the lung is often involved in systemic diseases, the pulmonary history should always be viewed in relation to other problems affecting the whole patient.

The physical examination of the lung is referenced to the time frames of inspiration and expiration, just as the cardiac examination is referenced to systole and diastole. In inspiration, the respiratory muscles are doing work, air is flowing through the airways, and with lung expansion, terminal gas exchanging units are opening. Air flows out through the airways during expiration, but expiration is normally passive, without perceptible muscle activity. Two-thirds of the normal respiratory cycle is spent in inspiration.

The major characteristic of the normal respiratory physical examination is symmetry. What is encountered on one side should be encountered on the other. What is perceived anteriorly should be perceived similarly when examining posteriorly. The examiner should be sensitive to small deviations from the symmetry normally seen from region to region, and some experience is necessary to distinguish a normal from an abnormal finding. The examiner should be alert to signs of increased work of breathing or respiratory distress and to the presence or absence of certain pathologic constellations, particularly consolidation, pleural effusion, and pneumothorax (Table 35.1).

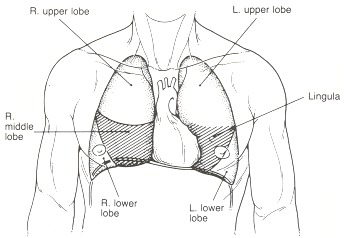

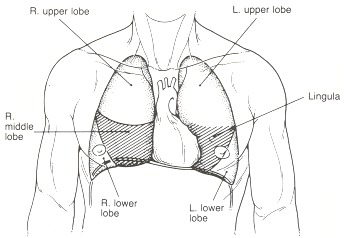

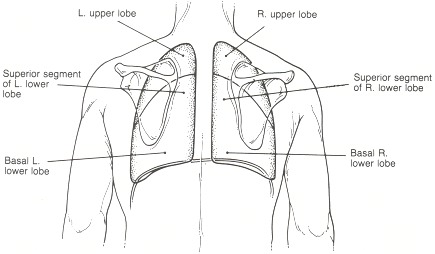

The respiratory examination is normally performed according to Osler's classic sequence of inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation (Table 35.2). All lobes of the lung should be systematically examined. The examiner should be aware of the surface projections of each of the five lobes (Figures 35.1 and 35.2). Findings should be compared left with right, upper with lower, and anterior with posterior.

The examination starts with a thorough inspection. With the patient seated or supine, the examiner begins, facing the patient, by counting the patient's respiratory rate, observing the rise and fall of the chest wall and abdomen. Fifteen to 30 seconds" observation should suffice. It should be noted whether any irregularities in the patient's respiratory rhythm are present (Chapter 43). The depth of inspiratory efforts should be noted and compared to the examiner's perception of normal. The relative time taken by the inspiratory and expiratory phases should be compared. Two-thirds of the respiratory cycle should normally be spent in inspiration (I:E = 2:1).

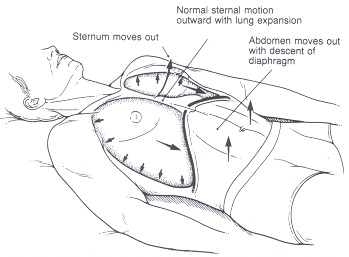

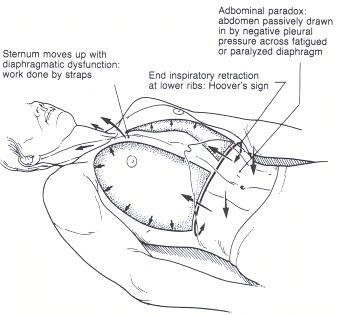

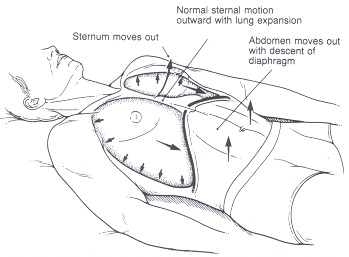

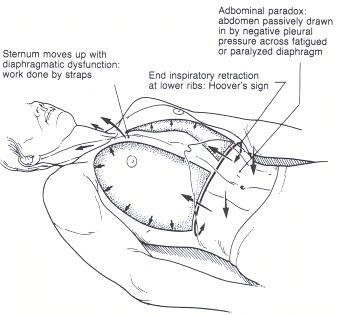

The examiner should next observe the pattern of respiratory muscle use. Normally, the diaphragm does all the work of inspiration and the abdomen will move outward along with the chest wall as the diaphragm descends (Figure 35.3). Inward inspiratory motion of the abdomen is termed abdominal paradox and suggests diaphragmatic dysfunction (Figure 35.4). Inward inspiratory motion of the chest wall is suggestive of a decrease in lung compliance. Placing the palms of the hands on the chest and abdomen may help confirm the visual impression. Active use of the abdominal musculature during expiration is distinctly abnormal. Look to see if the strap muscles of the neck, the scalenes, and the sternocleidomastoids are contracting during inspiration causing an upward motion of the entire chest. Use of accessory muscles is suggestive of increased inspiratory work of breathing.

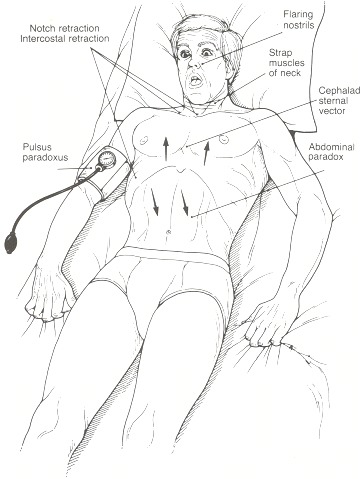

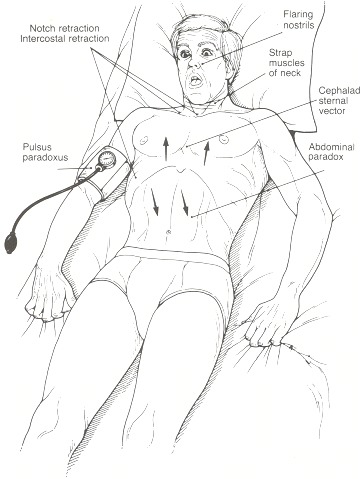

Extreme increases in inspiratory work of breathing may be reflected in accentuated swings of pleural pressure. Negative pleural pressure may be manifested by inspiratory retraction of the suprasternal or supraclavicular notches or the intercostal spaces. In the presence of notch retraction, pulsus paradoxus is frequently present and should always be measured (Figure 35.5).

Finally, the examiner should note whether the hemithoraces move equally and simultaneously and note whether any anomalies of the chest wall are present.

For the remaining phases of the examination—palpation, percussion, and auscultation—it is most efficient to complete the examination of the anterior chest, then ask the patient to sit upright and complete the examination of the posterior chest. The anterior chest examination covers the muscles of respiration, the trachea and major airways, the anterior upper lobes, and the right middle lobe and lingula, respectively. The posterior chest examination covers the posterior segments of the upper lobes, the superior segments of the lower lobes, and the posterior and lateral basal segments of the lower lobes.

Begin by establishing whether the trachea is in the midline. Place the thumb and index fingers of the examining hand on the lateral aspects of the trachea in the suprasternal notch and palpate the relative distances from the fingers to the borders of the sternocleidomastoid muscles. Normally, the trachea will be the midline and the distances will be equal.

Palpate the sternomastoid muscles themselves to determine whether they are tensing during inspiration reflecting accessory muscle use.

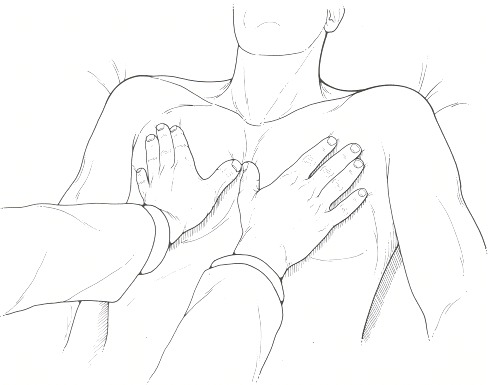

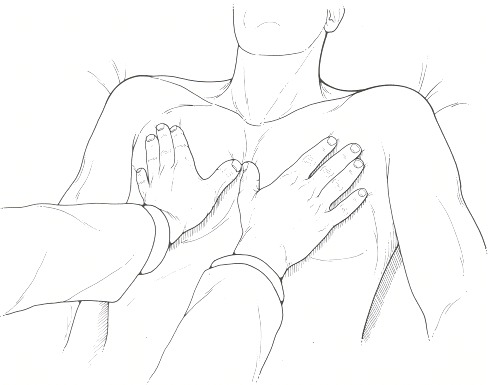

Next, the anterior chest should be palpated with the palms flat against the chest wall and the thumbs touching over the sternum to establish the midline (Figure 35.6). The hands should be placed at the angle of Louis, at the fourth to fifth intercostal space and again at the lower costal margin. The patient is asked to take slow deep breaths and the expansion of the hemithoraces should be observed with attention paid as to whether expansion is equal in amplitude and timing. The costal margin itself should be palpated to determine the presence of end-inspiratory retraction, or Hoover's sign. Hoover's sign suggests severe hyperinflation and air trapping (see Figure 35.4). Finally, the examiner's hands should be placed on the mid-chest in the midline and the upper abdomen to determine whether thoraco-abdominal dyssynchrony or paradoxical movements might be present, and to rule out active use of abdominal muscles during expiration.

Percussion of the thorax attempts to assess the state of the pulmonary parenchyma, whether it is filled normally with air, consolidated or hyperinflated. Percussion may also detect obliteration of the pleural space by fluid (pleural effusion) or by air (pneumothorax).

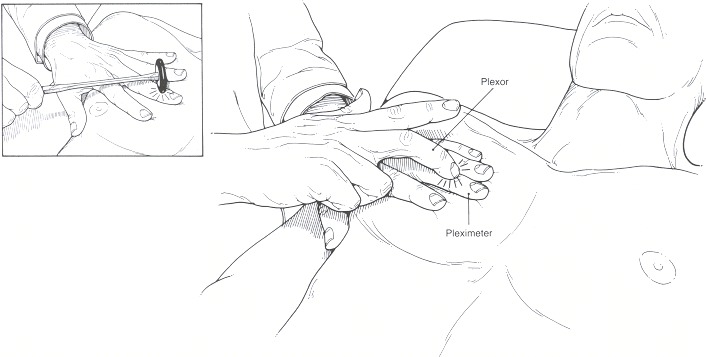

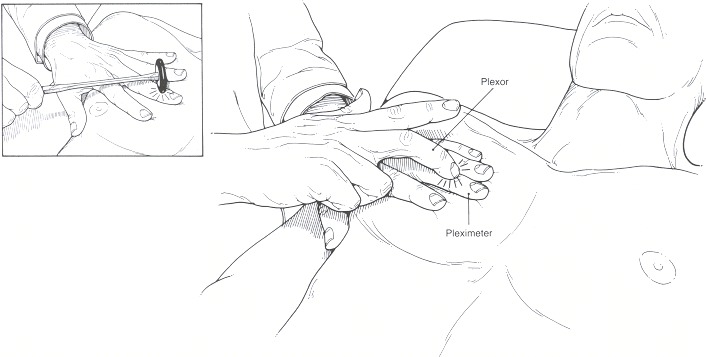

Percussion is performed during normal tidal breathing over the projection of each of the lobes (Figure 35.7). The percussion note is elicited by placing the distal ends of the middle and index fingers flat against the surface to be percussed. The distal interphalangeal joint of the middle or index finger (pleximeter) is sharply rapped by the corresponding finger tips of the opposite hand (plexor). The motion should be generated by flexion of the tapping wrist rather than by motion of the whole arm. For small examiners and large patients, a reflex hammer may be conveniently substituted for the tapping finger.

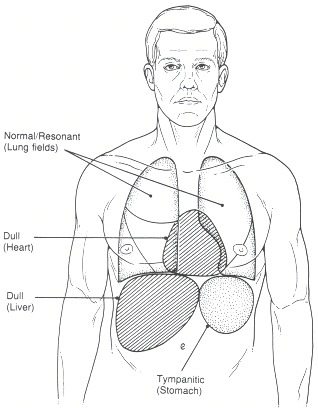

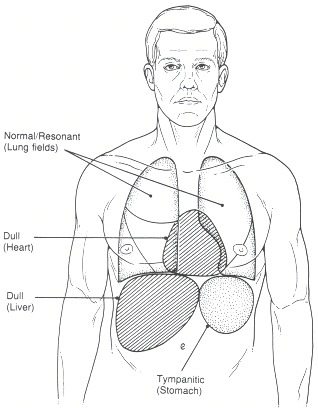

Percussion notes are described as normal or resonant, tympanitic, and dull. They may be compared with locations in which these notes normally occur (Figure 35.8). A normal percussion note is generally heard over the lung fields. A tympanitic or hyperresonant note can be elicited over the gastric air bubble just under the left hemidiaphragm and a dull percussion note is normally encountered over the liver.

The percussion note will also be dull over the cardiac borders in the left anterior chest. Otherwise, a normal note should be encountered throughout both hemithoraces.

Auscultation assesses the state of the airways and provides additional information about the state of the lung parenchyma. Like the findings from inspection, palpation, and percussion, normal findings are characterized by their symmetry. Auscultation is performed using the diaphragm of the stethoscope over the lobar projections in inspiration and expiration. The patient should be asked to breathe slowly and deeply through the mouth. Some patients may breath hold after inspiration and will need to be told to exhale. Simple requests such as "in" or "out" will usually suffice in these cases. The spontaneous respiratory rate may be estimated during auscultation in patients whose shallow breathing pattern makes measurement by inspection or palpation difficult. Remember to warm up the stethoscope before examining the patient.

Breath sounds are described according to their quality, intensity, transmission characteristics, and the presence or absence of extra (adventitious) sounds. Breath sounds are qualitatively described as normal (vesicular) or bronchial. Normal breath sounds can be compared to the sounds heard over the examiner's own chest provided no significant respiratory problems are present. Bronchial breath sounds are louder, higher pitched, harsher, and more immediate than normal vesicular sounds and ordinarily can be heard directly over the trachea. Unlike normal vesicular sounds, expiration is heard with particular clarity in bronchial breathing. Bronchial sounds anywhere else in the chest are abnormal and suggest consolidation of lung parenchyma. Sounds intermediate in quality are sometimes referred to as bronchovesicular.

The intensity of breath sounds relates to the amount of airflow in the region being examined and to the proximity of the lung to the examiner. Normally, sounds will be heard somewhat louder at the bases than in the upper lobes, reflecting the normal apical–basal gradient of regional ventilation. Some experience is necessary when asymmetric intensity is encountered to distinguish a regional increase in intensity from a decrease in other areas.

While listening to tidal breathing, the examiner should be alert to the presence of adventitious lung sounds, extra sounds associated with respiration. Crackles or râles are discontinuous monophonic sounds heard during inspiration that reflect the opening of closed terminal respiratory units. Wheezes are continuous polyphonic sounds heard during expiration that reflect narrowing of intrathoracic airways. Rhonchi are low-pitched continuous snoring sounds heard in either inspiration or expiration associated with uncleared secretions in the airways. Stridor is a wheezing sound most commonly encountered in extrathoracic airways and heard in inspiration. Stridor usually reflects extrathoracic airway obstruction but may be caused by a fixed obstruction anywhere in the tracheobronchial tree. Pleural rubs may be heard in either respiratory phase and sound like the rubbing of leather.

Transmission of spoken sounds will be influenced by the underlying parenchyma and the state of the pleural space. The normal air-containing lung and pleural spaces are relatively poor transmitters of sounds. This transmission may be decreased even further in the presence of excess air or fluid in the pleural space, and increased in the presence of consolidation. Transmission can be described as normal, increased, or decreased. Transmission can be tested by vocal fremitus, tactile fremitus, or whispered pectriloquy. Each has the same significance, and one or all may be tested on any one patient depending on the examiner's level of confidence with the findings elicited.

Traditionally, vocal fremitus is tested by listening with the diaphragm of the stethoscope over the projections of each lobe while asking the patient to repeatedly say "ninety-nine." Having the patient say "boy," "oil," or "Freud" will also work and more closely approximates the original technique of the nineteenth-century German physicians who introduced the method. Tactile fremitus may be evaluated by palpating the same areas of the chest with the palms of the hands while asking the patient to say the same words. The significance of fremitus is the same by either auscultation or palpation. Both modalities need not be checked in all patients, but in cases of uncertainty, the two methods reinforce each other.

Whispered pectriloquy is elicited by having the patient whisper "one, two, three" while the examiner listens with the stethoscope diaphragm over the projections of the lobes. Normally, the sounds will not be distinctly perceived, but the words may be clearly discernible in the presence of consolidation. Whispered pectriloquy has the same significance as increased fremitus and adds no new information to those approaches.

Egophony, or "E to A" change (the name is derived from the Greek for bleating of goats), is a special case of altered transmission. Consolidation or pleural effusions allow only certain sound frequencies to pass through to the examiner's ear and tend to distort the sound of the vowel "E" so that it is perceived by the examiner as "A" or "AAAH." Egophony is elicited while listening over the projection of the lobes with the stethoscope diaphragm and asking the patient to say "E."

Additionally, the forced expiratory time (FET) may give a clue to the presence of obstructive disease. Have the patient take in a full, deep inspiration and hold that breath. At command, have the patient exhale as hard and as fast as possible and keep squeezing until all air is gone. (This is the same as the forced expiratory maneuver of a pulmonary function test. If the patient has done that test before, it makes instructions easier.) Listen over the trachea while watching the second hand of a watch. All breath sounds should cease within 5 seconds. Continued airflow beyond that time suggests airways with long time constants of emptying and obstructive lung disease.

The posterior examination reflects thoracic structure as well, the posterior segments of the upper lobes, and the superior and basilar segments of the lower lobes.

During inspection, the examiner should observe whether both hemithoraces move simultaneously and to a similar degree. The presence of kyphosis, scoliosis, or other spinal anomalies should be noted. Any scars should be noted.

Palpation is performed similarly to the anterior chest examination. With thumbs positioned over the spine to mark the midline, the palms of both hands are placed over the posterior thorax to evaluate expansion of the chest. The examiner should note whether the hemithoraces move simultaneously and to a similar degree. The posterior chest should be palpated at the superior scapular border, lower scapular border, and lower costal margin, checking the upper lobes, superior segments of the lower lobes, and both bases.

The posterior chest should be percussed bilaterally over the posterior projection of lobes and segments (Figure 35.2).

Auscultation should repeat the examinations performed anteriorly.

The heart should be examined for signs of right heart failure or pulmonary hypertension, especially jugular venous distention (Chapter 19), pedal edema (Chapter 29), hepatomegaly and tenderness (Chapter 95), a sharp pulmonic component of S2 (Chapter 23), a palpable pulmonary artery impulse (Chapter 21), and the murmur of tricuspid insufficiency (Chapter 26).

Clubbing (Chapter 44) is a frequent concomitant of chronic inflammatory or neoplastic lung diseases, and hypoxemic lung disease may be accompanied by cyanosis (Chapter 45). Lymphadenopathy (Chapter 149) should be sought, particularly in the cervical triangles, supraclavicular notches, and axillae.

The pulmonary history and physical examination provide only part of the picture in the evaluation of respiratory complaints. The bedside examination must be correlated with the chest roentgenogram (Chapter 48), arterial blood gases (Chapter 49), and pulmonary function studies to derive a complete basis for the diagnostic process. The value of the roentgenogram in particular cannot be overestimated in the diagnostic process for diseases of the chest.

History

The lung does not produce a wide variety of symptoms. The cardinal symptoms of pulmonary diseases represent the final common pathways of a variety of processes. The constellation of symptoms, their time course and relative severity, however, remain the physician's first basis for the generation of diagnostic possibilities.Dyspnea (Chapter 36), the subjective sensation of difficulty in breathing, is probably the most common respiratory complaint and cannot be differentiated at first glance from dyspnea due to cardiac disease, neuromuscular weakness, or simple obesity. Dyspnea should always be quantified as to how much exertion is necessary to produce the sensation of breathlessness.

Wheezing and asthma (Chapter 37) point to the presence of an obstructive airway process but may be seen in heart failure as well. Wheezing may result from airway reactivity, airway narrowing, airway obstruction, compression, tumors, aspirated foreign bodies, as well as a variety of biochemical and immunologic insults. The time course of wheezing complaints and history of precipitating causes provide important information for interpretation.

Cough and sputum production (Chapter 38) are common to obstructive, inflammatory, infectious, and neoplastic pulmonary processes, as well as cardiac diseases and disorders of the ears, nose, and throat. Cough is a normal defense mechanism of the respiratory tract, but when increased in severity or frequency, cough can be a cause of disease as well as an indicator of disease. Sputum production reflects the presence of inflammatory, infectious or neoplastic disease in the airways or pulmonary parenchyma. The amount and character of sputum provide the physician with helpful clues to distinguish among possible etiologies.

Hemoptysis (Chapter 39) is never normal and can be a warning of a serious or even life-threatening respiratory disorder. Hemoptysis must be differentiated from hematemesis and from simple epistaxis, and must be quantified in terms of volume per 24 hours for adequate assessment.

Tobacco use (Chapter 40) is probably the most prevalent cause of chronic lung disease in the United States and the most important avoidable cause of respiratory morbidity today. The risk of serious pulmonary diseases including lung cancer and emphysema is directly related to the number of cigarettes a patient has smoked. Smoking should be quantified in terms of pack years, packs per day multiplied by the number of years smoked. Smoking of substances other than tobacco is also a potential cause of morbidity. Use of marijuana, cocaine, and other inhalable drugs should also be considered.

Environmental inhalation (Chapter 41) is a significant cause of respiratory diseases. Coal miners ("black lung"), quarry workers (silicosis), insulation installers and shipyard workers (asbestosis), and cotton mill workers (byssinosis) represent notable risk categories. A thorough work history should be a part of every clinical evaluation, especially when unexplained respiratory complaints are present. Environmental exposures may be either sustained or episodic. The examiner should inquire carefully about the relationship of symptoms to specific exposures. In particular, a detailed occupational history is important in patients where an etiology is not readily apparent. The actual job performed as well as job title should be explored.

Past pulmonary disease (Chapter 42) contributes background information that is helpful in assessing a current complaint. Knowledge of prior respiratory infections or prior chest film abnormalities is invaluable in the interpretation of a current problem.

In settings where tuberculosis remains prevalent, knowledge of a history of tuberculosis (Chapter 47), tuberculosis exposure, and tuberculin skin test results may prove crucial.

Symptoms of infections such as fever or chills may be important evidence in the evaluation of a productive cough, and the presence or absence of weight loss or loss of appetite may serve to underscore the seriousness of a particular complaint or objective abnormality. Because the lung is often involved in systemic diseases, the pulmonary history should always be viewed in relation to other problems affecting the whole patient.

Physical Examination

The only instrument required for physical examination of the respiratory system is a stethoscope. The examiner evaluates the function of the respiratory muscles, the airways, and the pulmonary parenchyma, looking for evidence of respiratory distress or increased work of breathing, evaluating the function and pattern of utilization of the respiratory muscles, and assessing the state of the airways and the lung parenchyma.The physical examination of the lung is referenced to the time frames of inspiration and expiration, just as the cardiac examination is referenced to systole and diastole. In inspiration, the respiratory muscles are doing work, air is flowing through the airways, and with lung expansion, terminal gas exchanging units are opening. Air flows out through the airways during expiration, but expiration is normally passive, without perceptible muscle activity. Two-thirds of the normal respiratory cycle is spent in inspiration.

The major characteristic of the normal respiratory physical examination is symmetry. What is encountered on one side should be encountered on the other. What is perceived anteriorly should be perceived similarly when examining posteriorly. The examiner should be sensitive to small deviations from the symmetry normally seen from region to region, and some experience is necessary to distinguish a normal from an abnormal finding. The examiner should be alert to signs of increased work of breathing or respiratory distress and to the presence or absence of certain pathologic constellations, particularly consolidation, pleural effusion, and pneumothorax (Table 35.1).

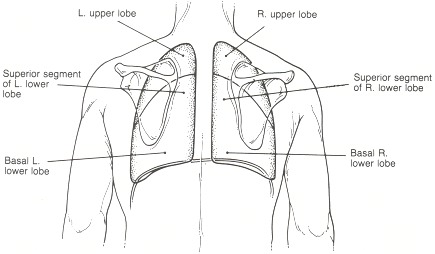

The respiratory examination is normally performed according to Osler's classic sequence of inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation (Table 35.2). All lobes of the lung should be systematically examined. The examiner should be aware of the surface projections of each of the five lobes (Figures 35.1 and 35.2). Findings should be compared left with right, upper with lower, and anterior with posterior.

The examination starts with a thorough inspection. With the patient seated or supine, the examiner begins, facing the patient, by counting the patient's respiratory rate, observing the rise and fall of the chest wall and abdomen. Fifteen to 30 seconds" observation should suffice. It should be noted whether any irregularities in the patient's respiratory rhythm are present (Chapter 43). The depth of inspiratory efforts should be noted and compared to the examiner's perception of normal. The relative time taken by the inspiratory and expiratory phases should be compared. Two-thirds of the respiratory cycle should normally be spent in inspiration (I:E = 2:1).

The examiner should next observe the pattern of respiratory muscle use. Normally, the diaphragm does all the work of inspiration and the abdomen will move outward along with the chest wall as the diaphragm descends (Figure 35.3). Inward inspiratory motion of the abdomen is termed abdominal paradox and suggests diaphragmatic dysfunction (Figure 35.4). Inward inspiratory motion of the chest wall is suggestive of a decrease in lung compliance. Placing the palms of the hands on the chest and abdomen may help confirm the visual impression. Active use of the abdominal musculature during expiration is distinctly abnormal. Look to see if the strap muscles of the neck, the scalenes, and the sternocleidomastoids are contracting during inspiration causing an upward motion of the entire chest. Use of accessory muscles is suggestive of increased inspiratory work of breathing.

Extreme increases in inspiratory work of breathing may be reflected in accentuated swings of pleural pressure. Negative pleural pressure may be manifested by inspiratory retraction of the suprasternal or supraclavicular notches or the intercostal spaces. In the presence of notch retraction, pulsus paradoxus is frequently present and should always be measured (Figure 35.5).

Finally, the examiner should note whether the hemithoraces move equally and simultaneously and note whether any anomalies of the chest wall are present.

For the remaining phases of the examination—palpation, percussion, and auscultation—it is most efficient to complete the examination of the anterior chest, then ask the patient to sit upright and complete the examination of the posterior chest. The anterior chest examination covers the muscles of respiration, the trachea and major airways, the anterior upper lobes, and the right middle lobe and lingula, respectively. The posterior chest examination covers the posterior segments of the upper lobes, the superior segments of the lower lobes, and the posterior and lateral basal segments of the lower lobes.

Examining the Anterior Chest

Palpation serves to reinforce the impressions generated from inspection and provides preliminary impressions about the state of the parenchyma that will be confirmed by percussion and auscultation.Begin by establishing whether the trachea is in the midline. Place the thumb and index fingers of the examining hand on the lateral aspects of the trachea in the suprasternal notch and palpate the relative distances from the fingers to the borders of the sternocleidomastoid muscles. Normally, the trachea will be the midline and the distances will be equal.

Palpate the sternomastoid muscles themselves to determine whether they are tensing during inspiration reflecting accessory muscle use.

Next, the anterior chest should be palpated with the palms flat against the chest wall and the thumbs touching over the sternum to establish the midline (Figure 35.6). The hands should be placed at the angle of Louis, at the fourth to fifth intercostal space and again at the lower costal margin. The patient is asked to take slow deep breaths and the expansion of the hemithoraces should be observed with attention paid as to whether expansion is equal in amplitude and timing. The costal margin itself should be palpated to determine the presence of end-inspiratory retraction, or Hoover's sign. Hoover's sign suggests severe hyperinflation and air trapping (see Figure 35.4). Finally, the examiner's hands should be placed on the mid-chest in the midline and the upper abdomen to determine whether thoraco-abdominal dyssynchrony or paradoxical movements might be present, and to rule out active use of abdominal muscles during expiration.

Percussion of the thorax attempts to assess the state of the pulmonary parenchyma, whether it is filled normally with air, consolidated or hyperinflated. Percussion may also detect obliteration of the pleural space by fluid (pleural effusion) or by air (pneumothorax).

Percussion is performed during normal tidal breathing over the projection of each of the lobes (Figure 35.7). The percussion note is elicited by placing the distal ends of the middle and index fingers flat against the surface to be percussed. The distal interphalangeal joint of the middle or index finger (pleximeter) is sharply rapped by the corresponding finger tips of the opposite hand (plexor). The motion should be generated by flexion of the tapping wrist rather than by motion of the whole arm. For small examiners and large patients, a reflex hammer may be conveniently substituted for the tapping finger.

Percussion notes are described as normal or resonant, tympanitic, and dull. They may be compared with locations in which these notes normally occur (Figure 35.8). A normal percussion note is generally heard over the lung fields. A tympanitic or hyperresonant note can be elicited over the gastric air bubble just under the left hemidiaphragm and a dull percussion note is normally encountered over the liver.

The percussion note will also be dull over the cardiac borders in the left anterior chest. Otherwise, a normal note should be encountered throughout both hemithoraces.

Auscultation assesses the state of the airways and provides additional information about the state of the lung parenchyma. Like the findings from inspection, palpation, and percussion, normal findings are characterized by their symmetry. Auscultation is performed using the diaphragm of the stethoscope over the lobar projections in inspiration and expiration. The patient should be asked to breathe slowly and deeply through the mouth. Some patients may breath hold after inspiration and will need to be told to exhale. Simple requests such as "in" or "out" will usually suffice in these cases. The spontaneous respiratory rate may be estimated during auscultation in patients whose shallow breathing pattern makes measurement by inspection or palpation difficult. Remember to warm up the stethoscope before examining the patient.

Breath sounds are described according to their quality, intensity, transmission characteristics, and the presence or absence of extra (adventitious) sounds. Breath sounds are qualitatively described as normal (vesicular) or bronchial. Normal breath sounds can be compared to the sounds heard over the examiner's own chest provided no significant respiratory problems are present. Bronchial breath sounds are louder, higher pitched, harsher, and more immediate than normal vesicular sounds and ordinarily can be heard directly over the trachea. Unlike normal vesicular sounds, expiration is heard with particular clarity in bronchial breathing. Bronchial sounds anywhere else in the chest are abnormal and suggest consolidation of lung parenchyma. Sounds intermediate in quality are sometimes referred to as bronchovesicular.

The intensity of breath sounds relates to the amount of airflow in the region being examined and to the proximity of the lung to the examiner. Normally, sounds will be heard somewhat louder at the bases than in the upper lobes, reflecting the normal apical–basal gradient of regional ventilation. Some experience is necessary when asymmetric intensity is encountered to distinguish a regional increase in intensity from a decrease in other areas.

While listening to tidal breathing, the examiner should be alert to the presence of adventitious lung sounds, extra sounds associated with respiration. Crackles or râles are discontinuous monophonic sounds heard during inspiration that reflect the opening of closed terminal respiratory units. Wheezes are continuous polyphonic sounds heard during expiration that reflect narrowing of intrathoracic airways. Rhonchi are low-pitched continuous snoring sounds heard in either inspiration or expiration associated with uncleared secretions in the airways. Stridor is a wheezing sound most commonly encountered in extrathoracic airways and heard in inspiration. Stridor usually reflects extrathoracic airway obstruction but may be caused by a fixed obstruction anywhere in the tracheobronchial tree. Pleural rubs may be heard in either respiratory phase and sound like the rubbing of leather.

Transmission of spoken sounds will be influenced by the underlying parenchyma and the state of the pleural space. The normal air-containing lung and pleural spaces are relatively poor transmitters of sounds. This transmission may be decreased even further in the presence of excess air or fluid in the pleural space, and increased in the presence of consolidation. Transmission can be described as normal, increased, or decreased. Transmission can be tested by vocal fremitus, tactile fremitus, or whispered pectriloquy. Each has the same significance, and one or all may be tested on any one patient depending on the examiner's level of confidence with the findings elicited.

Traditionally, vocal fremitus is tested by listening with the diaphragm of the stethoscope over the projections of each lobe while asking the patient to repeatedly say "ninety-nine." Having the patient say "boy," "oil," or "Freud" will also work and more closely approximates the original technique of the nineteenth-century German physicians who introduced the method. Tactile fremitus may be evaluated by palpating the same areas of the chest with the palms of the hands while asking the patient to say the same words. The significance of fremitus is the same by either auscultation or palpation. Both modalities need not be checked in all patients, but in cases of uncertainty, the two methods reinforce each other.

Whispered pectriloquy is elicited by having the patient whisper "one, two, three" while the examiner listens with the stethoscope diaphragm over the projections of the lobes. Normally, the sounds will not be distinctly perceived, but the words may be clearly discernible in the presence of consolidation. Whispered pectriloquy has the same significance as increased fremitus and adds no new information to those approaches.

Egophony, or "E to A" change (the name is derived from the Greek for bleating of goats), is a special case of altered transmission. Consolidation or pleural effusions allow only certain sound frequencies to pass through to the examiner's ear and tend to distort the sound of the vowel "E" so that it is perceived by the examiner as "A" or "AAAH." Egophony is elicited while listening over the projection of the lobes with the stethoscope diaphragm and asking the patient to say "E."

Additionally, the forced expiratory time (FET) may give a clue to the presence of obstructive disease. Have the patient take in a full, deep inspiration and hold that breath. At command, have the patient exhale as hard and as fast as possible and keep squeezing until all air is gone. (This is the same as the forced expiratory maneuver of a pulmonary function test. If the patient has done that test before, it makes instructions easier.) Listen over the trachea while watching the second hand of a watch. All breath sounds should cease within 5 seconds. Continued airflow beyond that time suggests airways with long time constants of emptying and obstructive lung disease.

Examining the Posterior Chest

The sequence of examination is now repeated posteriorly with the patient in a sitting position. Legs hanging over the side of the bed are probably easiest for the examiner but one may have to assist a sick patient to sit up in bed. Care should be taken to make sure that the patient does not lean to one side artifactually influencing the expansion of the chest and distribution of ventilation.The posterior examination reflects thoracic structure as well, the posterior segments of the upper lobes, and the superior and basilar segments of the lower lobes.

During inspection, the examiner should observe whether both hemithoraces move simultaneously and to a similar degree. The presence of kyphosis, scoliosis, or other spinal anomalies should be noted. Any scars should be noted.

Palpation is performed similarly to the anterior chest examination. With thumbs positioned over the spine to mark the midline, the palms of both hands are placed over the posterior thorax to evaluate expansion of the chest. The examiner should note whether the hemithoraces move simultaneously and to a similar degree. The posterior chest should be palpated at the superior scapular border, lower scapular border, and lower costal margin, checking the upper lobes, superior segments of the lower lobes, and both bases.

The posterior chest should be percussed bilaterally over the posterior projection of lobes and segments (Figure 35.2).

Auscultation should repeat the examinations performed anteriorly.

Additional Evaluation

With inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation of the anterior and posterior thorax, the physical examination of the respiratory system is complete. These data should not be viewed in isolation, and attention should be directed to physical findings associated with pulmonary diseases.The heart should be examined for signs of right heart failure or pulmonary hypertension, especially jugular venous distention (Chapter 19), pedal edema (Chapter 29), hepatomegaly and tenderness (Chapter 95), a sharp pulmonic component of S2 (Chapter 23), a palpable pulmonary artery impulse (Chapter 21), and the murmur of tricuspid insufficiency (Chapter 26).

Clubbing (Chapter 44) is a frequent concomitant of chronic inflammatory or neoplastic lung diseases, and hypoxemic lung disease may be accompanied by cyanosis (Chapter 45). Lymphadenopathy (Chapter 149) should be sought, particularly in the cervical triangles, supraclavicular notches, and axillae.

The pulmonary history and physical examination provide only part of the picture in the evaluation of respiratory complaints. The bedside examination must be correlated with the chest roentgenogram (Chapter 48), arterial blood gases (Chapter 49), and pulmonary function studies to derive a complete basis for the diagnostic process. The value of the roentgenogram in particular cannot be overestimated in the diagnostic process for diseases of the chest.

Figures

Figure 35.1Anterior surface projection of pulmonary lobes

Examination of the chest anteriorly primarily reflects the anterior segments of the upper lobes, the right middle lobe, and the lingula. Note the minimal projection of the lower lobes on the anterior chest.

Figure 35.2Posterior surface projection of pulmonary lobes

Examination of the posterior thorax reflects the posterior segments of the upper lobes and the superior segments and posterior basilar segments of the lower lobes.

Figure 35.3Normal inspiration

Descent of the diaphragm raises intra-abdominal pressure moving the abdomen outwards along with chest expansion. The sternum moves outward.

Figure 35.4Abnormal inspiratory findings

In the hyperinflated patient with obstructive lung diseases the flattened diaphragm pulls in the lower ribs at end-inspiration (Hoover's sign). The sternum is pulled cephalad by the action of the strap muscles of the neck. The abdomen may be retracted by the passive transmission of intrathoracic pressure across the dysfunctional diaphragm.

Figure 35.5Findings in acute respiratory distress

Tachypnea, anxiety, air hunger, flaring alae nasi, marked use of strap muscles of the neck, suprasternal and supraclavicular notch retraction. The sternum tends to move upwards due to the action or the strap muscles. In the event of diaphragmatic dysfunction, the abdominal wall is pulled in by the negative pressure accompanying chest expansion.

Figure 35.6Palpation of the chest

Hands should be placed at the same level with thumbs over the sternum anteriorly or the spine posteriorly (not shown) to avoid artifactual asymmetry of chest motion. The patient should be seated upright or prone or supine.

Figure 35.7Technique for percussion

The percussing finger (plexor) should be sharply struck against the distal interphalangeal joint of the middle finger of the opposite hand (pleximeter). The motion should be generated at the wrist rather than with the whole arm. (Inset): For small examiners and larger patients, use of a reflex hammer as a plexor may provide a more satisfactory percussion nate.

Figure 35.8Normal location of percussion notes

Normal resonance may be heard over the anterior and posterior lung fields. A dull percussion note can be elicited over the heart and liver. The stomach when full of air may produce a hyperresonant or tympanitic note.

Tables

Table 35.1Major Diagnostic Complexes in the Evaluation of Pulmonary Disorders

| Percussion | Transmission | Quality/intensity | Adventitioussounds | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consolidation | Dull | ↑ ↑ ↑ ↑ | Bronchial, ↓ | Râles |

| Atelectasis | Dull | ± | ↓ | Râles |

| Pleural fluid | Dull | Egophony, ↓ | Vesicular, ↓ | Rub |

| Pneumothorax | Tympanitic | ↓ | Vesicular, ↓ | – |

Table 35.2Sequence of the Respiratory Examination

| Patient supine or seated, examining anteriorly |

| Inspection: |

Respiratory rate, depth Respiratory rate, depth |

Muscle use Muscle use |

Respiratory distress Respiratory distress |

Chest wall anomalies Chest wall anomalies |

| Palpation: |

Tracheal position Tracheal position |

Thoracic excursion Thoracic excursion |

Abdominal, costal paradox Abdominal, costal paradox |

| Percussion |

| Auscultation |

| Patient in sitting position, examining posteriorly |

| Inspection: |

Anomalies of spine and back Anomalies of spine and back |

| Palpation: |

Thoracic excursion Thoracic excursion |

| Percussion: |

Diaphragmatic excursion Diaphragmatic excursion |

| Auscultation: |

Breath sounds, adventitious sounds Breath sounds, adventitious sounds |

Transmission of sounds Transmission of sounds |

Copyright © 1990, Butterworth Publishers, a division of Reed Publishing.

I have been searching to find a comfort or effective procedure to complete this process and I think this is the most suitable way to do it effectively.Thanks for shearing.

Trả lờiXóamajor ports in india